Michela Wrong’s new book, Do not Disturb, is the story of a political murder and an African regime gone bad.

The writer, who has made a career trading in demeaning stereotypes of Africans in previous works that include In the Footsteps of Mr Kurtz about the last days of Zairean president Mobutu Sese Seko, and It’s our Turn to Eat billed as “an analysis of why Kenya descended into political violence”, is at it again. This time she has the president of Rwanda in her crosshairs.

In Wrong’s words, the Congolese have been portrayed in barely disguised terms as a people that only like to have a good time, and dance in the bars as if there isn’t a worry for tomorrow although their ruler long ago took the country to the cleaners. As for any Kenyan that goes into politics, especially members of the Kikuyu community, the takeaway is that in them corruption is a near congenital illness.

But in none of her previous books is the British journalist’s racist stereotyping of an African people more pronounced than in Do Not Disturb.

The book opens by calling all Rwandans, literally, liars. Wrong, of course, has a character witness. It is none other than Ewart Grogan, like Wrong, a white Briton. Citing a trip to Rwanda in 1899, Wrong writes that Grogan “railed bitterly about the mendacity” of local guides. “Lies, lies, lies, I was sick to death of them. Of all the liars in Africa, I believe the people of Ruanda are by far the most thorough,” Wrong quotes Grogan.

Kenyans know Grogan as one of the most brutal colonial settlers. In March 1907, Grogan brutally whipped three Kenyan porters, crippling two and causing the death of another. Their crime? They had given Grogan’s sister and her friend too bumpy a ride in the rickshaw! You have to marvel that, in the 21st century, Wrong passes off the racist rantings of Grogan as confirmation of what she herself has to say about Africans. Even more astonishing is that the editors and publishers saw no problem with this.

Murder in South Africa

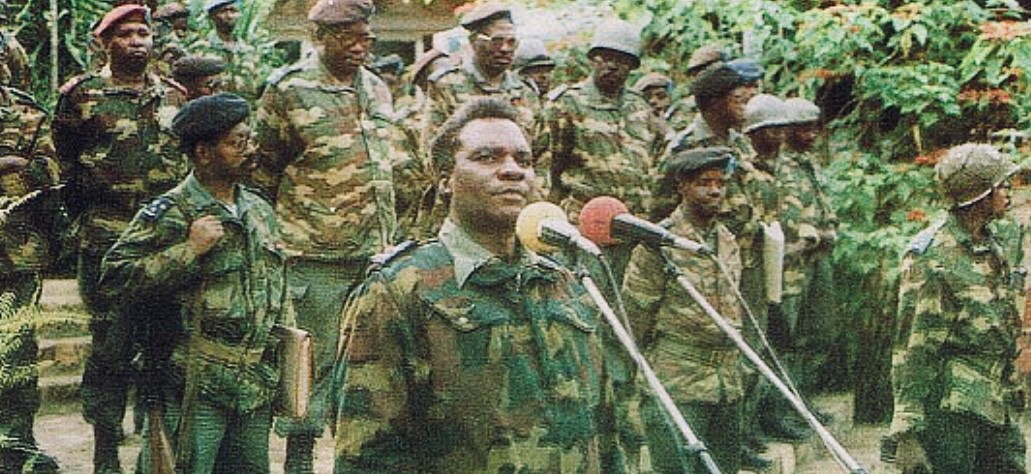

Do Not Disturb centres on the murder of Patrick Karegeya, a former Rwandan intelligence chief, in a hotel room in Johannesburg on New Year’s Day 2014 — a crime that Wrong flatly accuses, in fact indicts, President Paul Kagame for.

South African authorities — including the elite Hawks, equivalent of the FBI — investigated the crime but were unable to reach any conclusion to indicate anyone from Rwanda was responsible. On January 19, 2019, the Randburg Magistrates Court ruled that it was striking the murder inquest from its rolls.

When he fled to South Africa in 2007, Karegeya declared violent insurrection. He and his friend Kayumba Nyamwasa — also a former member of the Rwandan military — co-founded a political group, Rwanda National Congress (RNC), in 2010. Its purpose, they declared, “was to take power in Rwanda, by any means possible”. But would this be the basis for one to declare Rwanda the culprit in Karegeya’s demise? We are not talking of conversations in bars, but the authoritative words of an established author.

Wrong’s sources throughout the book should raise an eyebrow. First up are Karegeya’s family and close circle: his wife, his (grown) children, his surrogate son, his partner Nyamwasa, even his mother. In other words, people with a sense of grievance, and those with the most interest in demonising President Kagame.

Wrong did not speak to anyone in the government, and early in the book pre-empts questions about her choice with an unconvincing explanation.

Over the years, however, the narratives Wrong adopts, and promotes, aimed at delegitimising the administration in Kigali have unravelled. Take the biggest issue, the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi. Even before Genocide began, the extremist Hutu Power planners had designated the RPF as the perpetrator. This myth continued and was amplified in the countries to which the biggest suspects had fled — mainly France — where the family of the former president Habyarimana had settled, along with key former officials.

The RNC continues to push this conspiracy theory, and have found an enthusiastic megaphone in Wrong.

But two French magistrates, Marc Trevidic and Nathalie Poux in 2017, declared there was no way the RPF could have brought down Habyarimana’s plane. No prizes for guessing why Wrong fails to mention any of the reports that discredit what her friends have told her.

Admitting one truth sends wrong’s whole case cascading, like a house of cards

source:greatlakeseyes